We are now going to start looking at algorithms. An algorithm is, as we have seen, a clearly-defined solution to a particular problem, which follows a series of clearly-specified steps. Common examples of algorithms include sorting collections of data, or searching for an item in a collection of data.

We will start by looking at algorithm efficiency using the Big O notation, and then look at some sorting and searching algorithms, comparing their efficiency.

When designing algorithms, we need some measure of how complex an

algorithm is. Complexity can be measured in various ways, for example

performance (time taken), or memory usage. The standard for measuring

algorithm complexity is known as the Big O notation. This is a measure

which expresses complexity in relation to some property n. This property

depends on exactly what we are trying to do. For a sorting algorithm, which

sorts a list, for example, it could be the number of items in the list. For

indexing a list or linked list, it could also be the number of items in the list; the larger the list, the more items we potentially have to traverse to reach a given index.

"Big O" notation is expressed in terms of this property n. For example

we can have:

O(1) : if an algorithm is O(1) it means that its complexity is independent of n. Calculating the memory address of the index of an array would be an example of an O(1) operation because it is always given by the equation:memory_address = start_memory_address + index * bytes_used_by_one_item

Clearly the time taken to evaluate this equation does not depend on the

size of the list, which is the property n in this case. Even if the list is very large, and the index is very large, we can quickly calculate the item's address using the simple equation above. O(1) algorithms are thus highly efficient… but not many algorithms are O(1)!

O(n) : if an algorithm is O(n) it means that its complexity depends on

the value of n directly, or linearly.

So if n increases by 2, the complexity will also

increase by 2 Indexing a linked list is a good example of an O(n)

algorithm because we have to manually follow the links to retrieve the item

with a given index - we cannot rely on consecutive memory addresses. So

complexity of linked list indexing is related linearly to the length of the

list.This brings up an important point, the big O notation used is the worst-case scenario. In a basic search such as this, we assume the index will not be found until the end of the list in which case we will have to search through n items, where n is the number of items in the list.

A basic search for an item in a list, in which we loop through all members of the list until we find the search term we are looking for, is also O(n): it's again linearly related to the length of the list, because in a worst-case scenario, we will have to search through the entire list before we find the item.

O(n^2) (^ indicates "power"): if an algorithm is O(n^2) then the time taken or memory used is most influenced by the square of the number of items. So if the number of items doubles, then the time taken will increase around four times. Or if the

number of items increases by 10, the time taken will increase around 100 times.Algorithms which have an outer and inner loop, in which we have to loop through an array twice, are of this kind. The outer loop has to be run n times,

but the inner loop has to be run n times each time the outer loop runs.

So the time taken is proportional to n^2. For example, below is some code

with two loops, an outer and inner loop. An algorithm do_something() is

performed n^2 times (16 times in the example, as n is 4). If n is changed

to 5, then the operation will be performed 25 (5^2) times.

n = 4

for i in range (n):

for j in range (n):

do_something(i, j)

Clearly it can be seen that O(n^2) algorithms are not efficient, and should

be refactored to a more efficient algorithm e.g. O(n) or, as described

below, O(log n).

O(n^2) algorithms are known as quadratic because their complexity can be calculated using a quadratic equation an^2 + bn + c. It should be noted that,

depending on the exact algorithm, the complexity will not be exactly

n^2. However it will be something close to n^2 which can be expressed

using a quadratic equation. If you consider a quadratic equation, it can be

seen that, as the variable n increases, the n^2 term will come to

dominate the result.

3n^2 + 6n + 7

for the value n=100 will be:

3(100^2) + 6(100) + 7

which is

30000 + 600 + 7

It can be seen that the n^2 term dominates. Remember we said above that

in Big O notation, we need to worry about worst-case scenarios (scenarios with

large n typically) as these will be the main source of inefficiencies.

So it can be seen that, in these worst-case scenarios, even if the complexity

is not exactly n^2, it will approximate to it. So, such algorithms are still designated O(n^2).

Essentially, when considering complexity with the Big O notation, we divide algorithms into classes, and ask ourselves which class (e.g. O(1), O(n), O(n^2) etc) does the algorithm fall into, depending on the behaviour of the algorithm

for large n. We are less interested in an absolute value for the time taken, or memory used, to complete an algorithm and more interested in the algorithm's behaviour for very large values of n, so we can see what happens in worst-case scenarios.

The diagram below shows how complexity increases with increasing n for

different classes of Big O complexity:

n is along the x (horizontal) axis, while the complexity is along the y (vertical) axis;O(n);O(n^2);O(log n); to be discussed below;0.5*n^2 + 0.5n. This shows that the quadratic form is exhibited, and the shape of the graph, with a rapid increase with the rate of increase getting bigger with larger values of n is very similar to n^2. (This is known as a parabolic graph). So, even if the complexity is not exactly O(n^2), the behaviour of the graph for increasing n is essentially the same as O(n^2).O(log n): if an algorithm ia O(log n) it is related to the logarithm

of n. Logarithm is the inverse operation to power, and is always expressed in

terms of a particular base. A logarithm of a given number (relative to a particular base, such as base 10 or base 2) will give you the power the base has to be raised to, to give that number. So if b to the power p equals x, then log(b)x = p.b^p = x => log(b) x = p

In Big O notation, the base is 2. So for example, if:

2^2 = 4

2^3 = 8

so:

log(2) 4 = 2

log(2) 8 = 3

Hopefully you can see from this that an O(log n) operation is relatively

efficient, because we can increase n significantly but the time taken, or

memory consumed, will increase much less. For example, to perform an

O(log n) operation on a list of 256 (2^8) items will only take twice as long as a list of 16 (2^4) items. Constrast that to an O(n) algorithm which will take 16 times as long (because 16 x 16 is 256). So if you can refactor an algorithm from O(n) to O(log n), it is clearly desirable.

You should be able to see that an O(log n) operation has an initial fast increase in complexity which then flattens out. Algorithms which involve one complex operation which must be done once, or a small number of times, no matter what the value of n, followed by a less-complex operation, will typically be of the form O(log n).

We are now going to start looking at sorting algorithms, and consider the Big O complexity of each algorithm we examine.

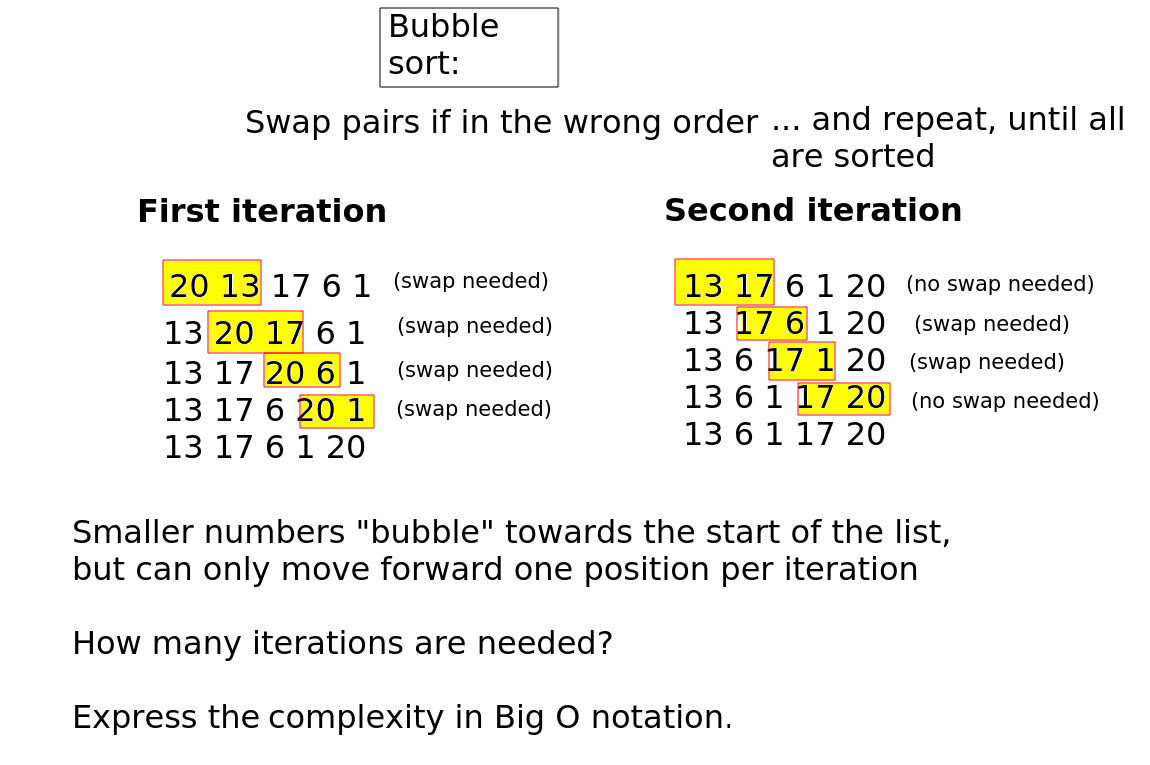

We are now going to look at various sorting algorithms and express their complexity in Big O notation. The first algorithm we will look at is the bubble sort. This is a simple algorithm, but it is not very efficient. As you can see from the diagram below, it involves looping through a list and considering each pair of values in turn. If the pair is in the correct order, we do nothing. If it is not, we swap them.

As you can see from the diagram, larger numbers "bubble" towards the end of the list, for example the value 20 will, each time a swap is done, move one position onwards in the list. So once we've finished the first iteration of the sort, the largest value will be in the correct position. However, you should also be able to see from the diagram, and appreciate from the way the algorithm works, that the smaller values only move forward one position per iteration (i.e. one position per loop). So once we've finished the loop, the value 1 will only have moved forward one place.

So we then need to iterate (loop) again through the list, and perform another series of swapping operations. You can see this on the "second iteration" part of the diagram. This results in the smaller numbers again moving forward just one position.

We'd therefore need to implement this using a loop within a loop. The outer loop would be the successive iterations, whereas the inner loop would be used to perform the swapping operations of one particular iteration of the algorithm.

It should be noted that on the first iteration of the bubble sort, the largest value will be correctly in place at the end of the list. So on the second iteration, we do not need to consider the last position in the index; for example if there are 5 values, we only need to consider 4 in the second iteration. Similarly, at the end of the second iteration, the second-biggst value will be correctly placed, so on the third iteration we do not need to consider the final two values of the list.

Bubble sort (and many other sorts) require variables to be swapped. How can we do this? We would use code such as this, involving the creation of a temporary variable.

tempVar = a

a = b

b = tempVar

We cannot just do:

a = b

b = a

because the first statement will set a to b before we've saved the value

of a anywhere else, so when we execute the statement b = a we will set

b to its original value, because we a now contains the value of b.

The use of a temporary variable, as in the correct example, means we can

store a before assigning the variable a to the value of b, which means

we do not lose the original value of a.

However, in Python there is a shortcut for swapping variables which does this for us:

a,b = b,a

On paper, continue the iterations of bubble sort to sort the values. After how many iterations are the values completely sorted?

How could we express the time taken in terms of n, i.e. the number of items

in the list?

What, therefore, would be the complexity in Big O notation of this algorithm, where n is the number of values in the list?

Have a go at coding bubble sort in Python. You should create a list of numbers to sort, and once the algorithm has finished, print the list to test whether the sort has taken place. If you are struggling, try writing it in pseudocode first.

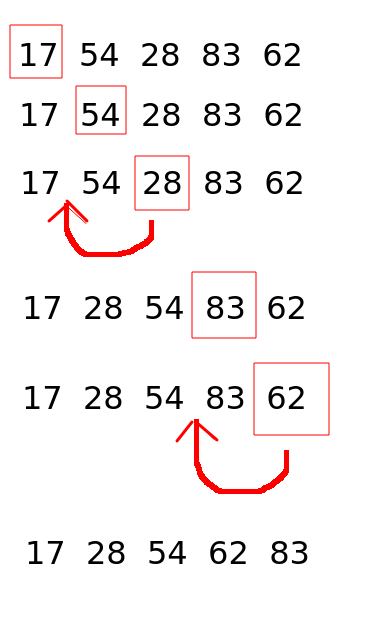

Selection sort is another sorting algorithm which is conceptually simple but (relatively) inefficient. Nonetheless it has some advantages over bubble sort,

in particular, the number of swap operations is minimised (of order O(n) rather than O(n^2)), and will be used as another example of a sorting algorithm.

We once again have an outer loop. This loops through each member of the list (apart from the last). Within the outer loop we have an inner loop which compares the current member with each of the remaining members in turn. The lowest remaining member is found, and if this is lower than the current member, the current member and this lowest member is swapped.

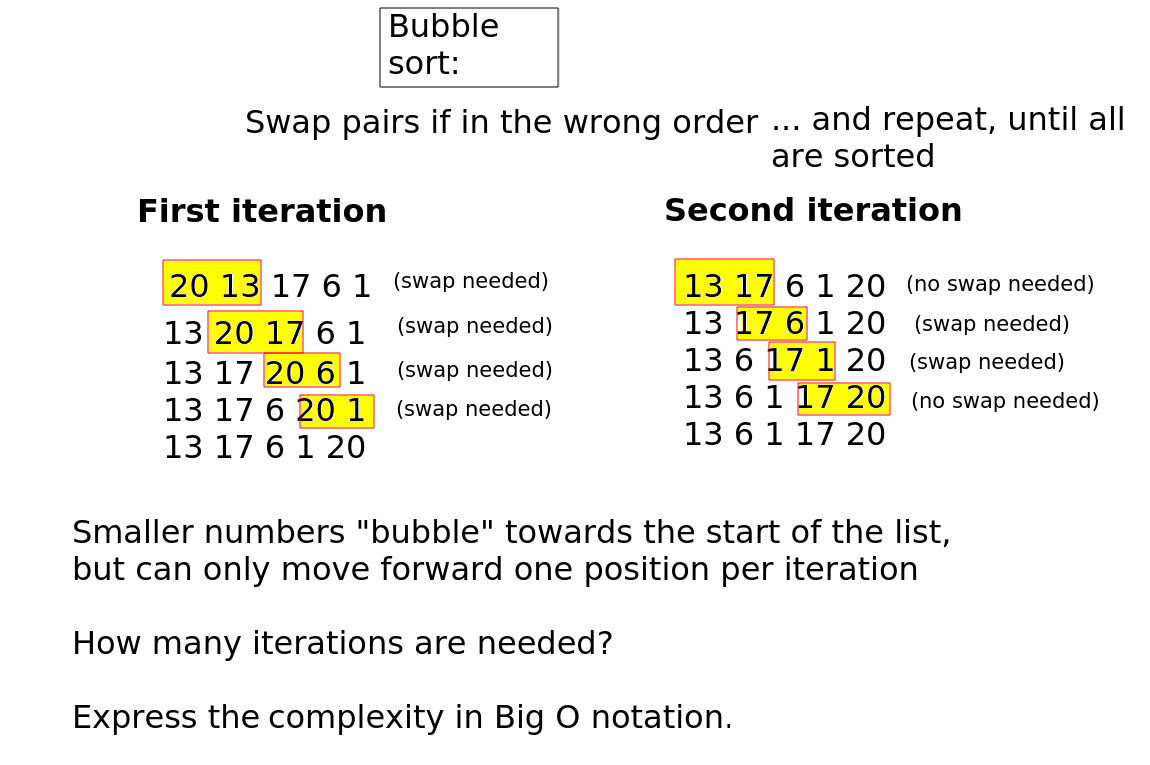

See the diagram below, which is based from notes provided by my former colleague Brian Dupée, which were in turn sourced from the site sorting-algorithms.com (this site still exists, provided by Toptal, but does not appear to contain these resources anymore)

It is of interest what this algorithm's time complexity equals, as it raises an important conceptual point about the Big O notation. If you imagine sorting 5 values, what needs to be done?

n-1, or 4 swaps.So the total number of operations for a 5-member list is 4+3+2+1, or more generally for an n-member list, the number of operations is the sum of all the numbers from 1 to n. This value is equal to (n + n^2) / 2.

This is an equation of quadratic form, as it can be expressed instead as 0.5n^2 + 0.5n. So with large n values the n^2 term will dominate, and thus, this is an O(n^2) class of algorithm, i.e. less efficient. It is not quite as inefficient as bubble sort, particularly given that less swaps are involved (swapping is a relatively expensive operation as it requires a temporary variable to be created), but it can still potentially be improved.

A less mathematical way of thinking about it is to consider the fact that there are two loops, one within another. Algorithms of this form - even if one of the loops does not iterate through the entire list - will generally be O(n^2).

When swapping numbers, swapping is not particularly computationally expensive. However, if the two values are complex objects which take time to initialise, then the fact that we need to create a temporary variable can mean a swap is expensive. So in cases like this, selection sort is particularly favoured over bubble sort.

Have a go at implementing selection sort in Python.

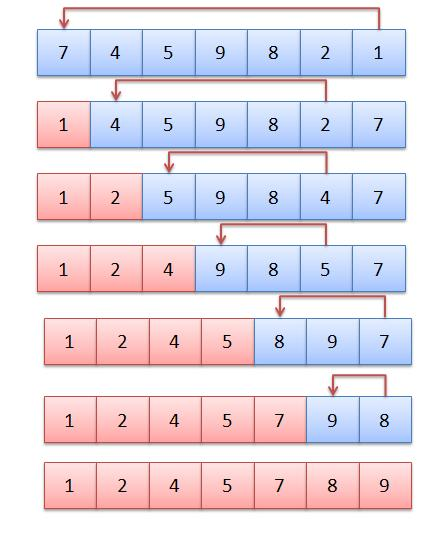

A third type of simple sort, with complexity O(n^2) in many cases, but occasionally O(n) (see below), is the insertion sort. This is shown on the diagram below.

Insertion sort works by progressively inserting values into the list at the correct place. A typical implementation will work through a list and sort it in-place (i.e. within the original list, rather than creating a new list), by defining a "divider" that separates out the list into sorted and unsorted parts. The "divider" moves forward one position on each iteration of the outer loop. The "divider" is shown by a red box in the diagram.

Each time we move to a new "divider", we compare the "divider" with the sorted part of the list, to its left. If all members of the sorted part are less than the "divider", we do nothing. If on the other hand we find a member, or multiple members, of the sorted part of the list which are greater than the "divider", then we insert the "divider" into the sorted part at the appropriate place, and move all the remaining members on one place. This is done with the values 28 and 62 in the diagram above. This operation would be done using an inner loop, starting at the divider and moving back through the sorted part while there are values greater than the "divider". As soon as we find a value less than the "divider", we have our insertion position.

Note that we can perform a useful "trick" here which can prevent us having to do the inner loop at all. If the last value of the sorted part of the list - which will be the value immediately to the left (i.e one index below) the "divider", is less than the "divider", then we know that the "divider" is already in its correct position. This is because the sorted part of the list is sorted, and the highest value within the sorted part will be immediately to the left of the "divider". So if the "divider" is greater than this value, we do not to move it. Thus, we do not need an inner loop.

You should always be on the lookout for "tricks" like this when designing algorithms. Is there something about the data which means that, in some cases, we can avoid having to perform computationally expensive operations like an additional loop, and therefore reduce the complexity of the algorithm?

The consequence of this is that if the list is "almost sorted", then the complexity will be closer to O(n) than O(n^2), as in most cases, we will not need an inner loop. So if, for whatever reason, we know that our list is almost sorted already, an insertion sort is a strongly favoured choice.

Have a go at implementing insertion sort in Python.